If you’ve followed along with Project Track Attack, then you know that we’ve touched on every part of the drivetrain except the engine. Aside from a FAST EZ-EFI install back in 2012, the old 318 Polyhead has remained as it was installed a decade ago, and we’ve done very little to it. Its limitation on horsepower has brought us to where we are now – a solid, reliable powerplant that has served us well, but we need more power.

If you’ve followed along with Project Track Attack, then you know that we’ve touched on every part of the drivetrain except the engine. Aside from a FAST EZ-EFI install back in 2012, the old 318 Polyhead has remained as it was installed a decade ago, and we’ve done very little to it. Its limitation on horsepower has brought us to where we are now – a solid, reliable powerplant that has served us well, but we need more power.

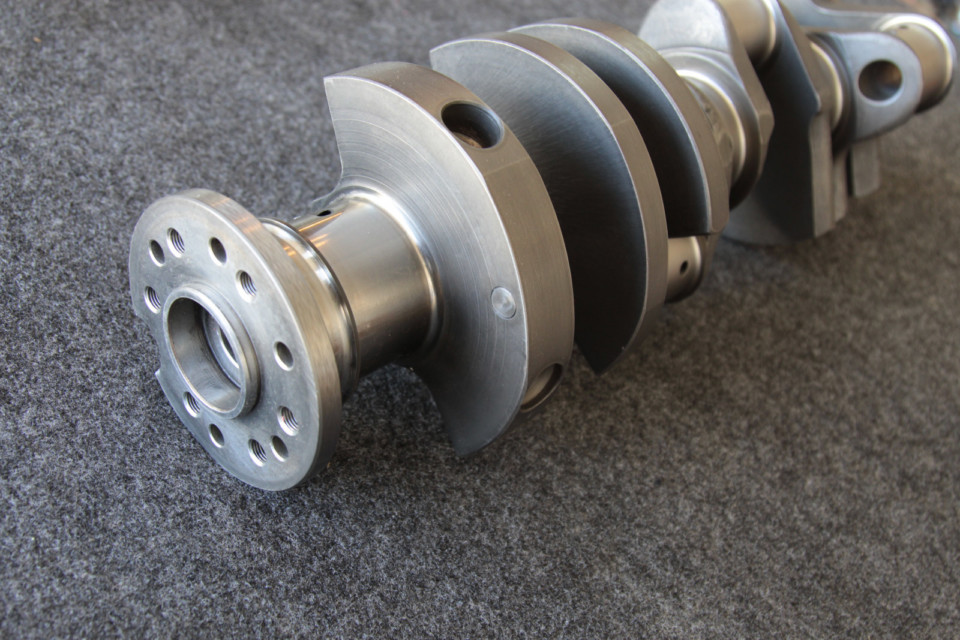

For that, the Polyhead has to go and in its place comes another unique build that we set in stone about a year ago, starting with a 1973 LA 360 block. For the short-block build, we enlisted the help of some popular companies that we couldn’t do this build without. Scat Crankshafts for our rotating assembly, JE Pistons to plug the holes, and to put everything together we relied only on ARP Bolts.

Whether you want 12-point or 6-point, polished or black oxide, ARP Bolts has a set for most every engine. While our bottom end is pure early 360 Mopar LA series, the top end is another ball of wax. Many bolts will cross over, but to play it safe we ordered a couple of extra kits to make sure.

The goal for Project Track Attack has always been to find improvements that allow us to go faster, handle better, and spank the living you-know-what out of modern muscle cars and Porsches at Willow Springs. We’ve made some great friends (and a few enemies) while navigating the 2.5-mile road course, and we’ve reduced our lap times by over 11 seconds since we first hit the track with our near-stock 1965 Plymouth Belvedere II in 2013.

The last major improvement included a full coilover suspension from Control Freak Suspensions and much wider, stickier tires in the form of Falken’s Azenis, mated to wider Weld Racing S76 wheels. This combination alone took us through all nine turns slightly over four seconds quicker than our previous romp. While the upgrades are impressive and illustrate how handling and performance have improved with our upgrades, it’s time to step up our game and lay down a few more ponies with a 408ci LA series small-block.

Choosing The Engine

With Mopar, it seems there are really three old school engine choices, and one modern engine choice. So, the first step is to determine what suits your driving style, how you’re using the car, and what kind of horsepower you want. If you just want bragging rights for what you put down on the rollers and money is no object, have at it and get a big-block crate engine, or better yet, get a Hemi. If you want something more practical, and you don’t care about impressing every Joe Blow out there with 1,200 horsepower, then you’re in the place we’ve come to with our small-block build.

Rather than showing you step by step how to bolt everything together, we wanted to take this from the viewpoint of a first build. You get what you get with crate engines, but we had some specifics for this build. We wanted to stay old school, and since we’re road racing and taking long trips, Mopar’s LA series small-block seemed to make more sense. So we checked with our Mopar friends and got some solid advice on where to start on our 408ci stroker.

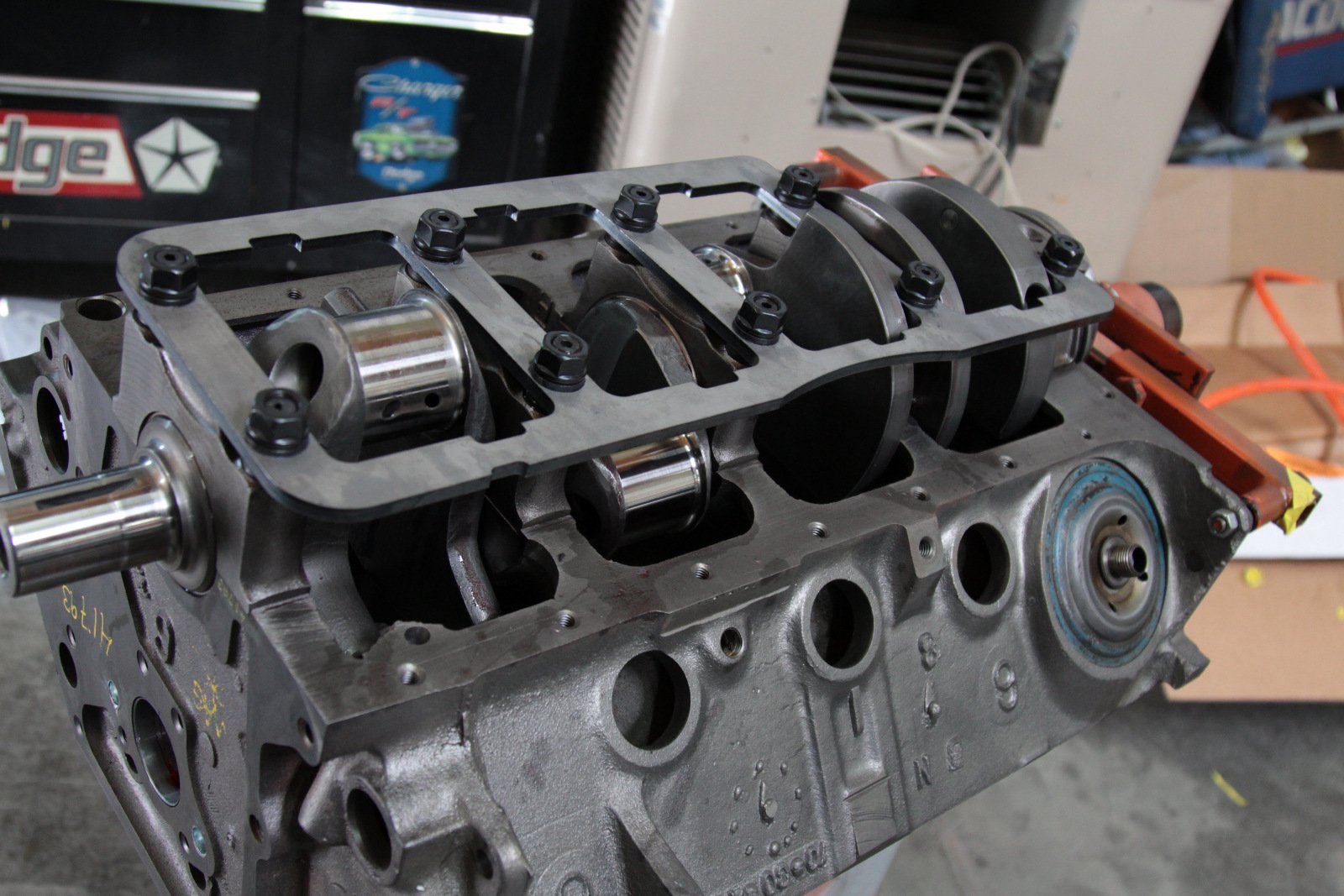

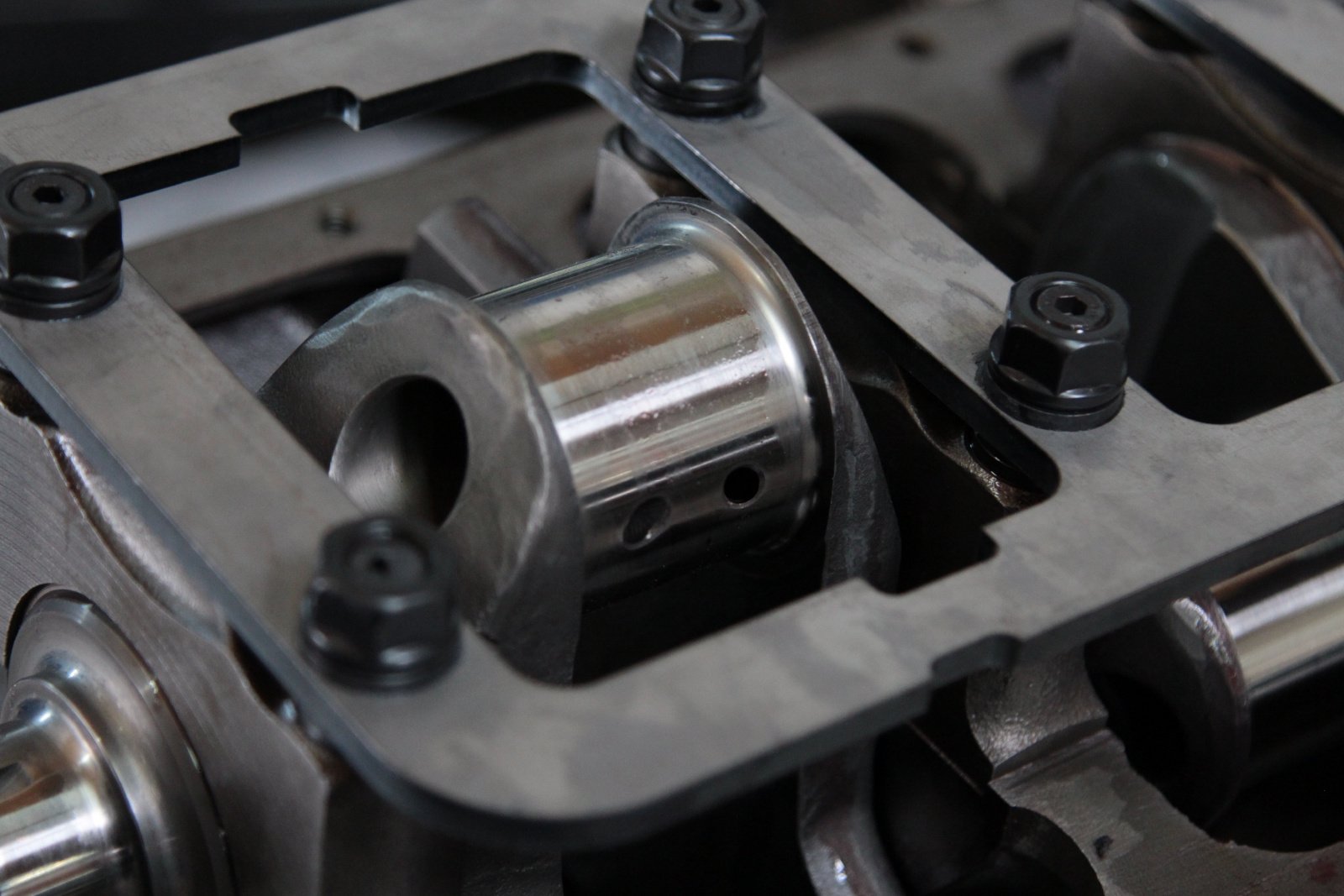

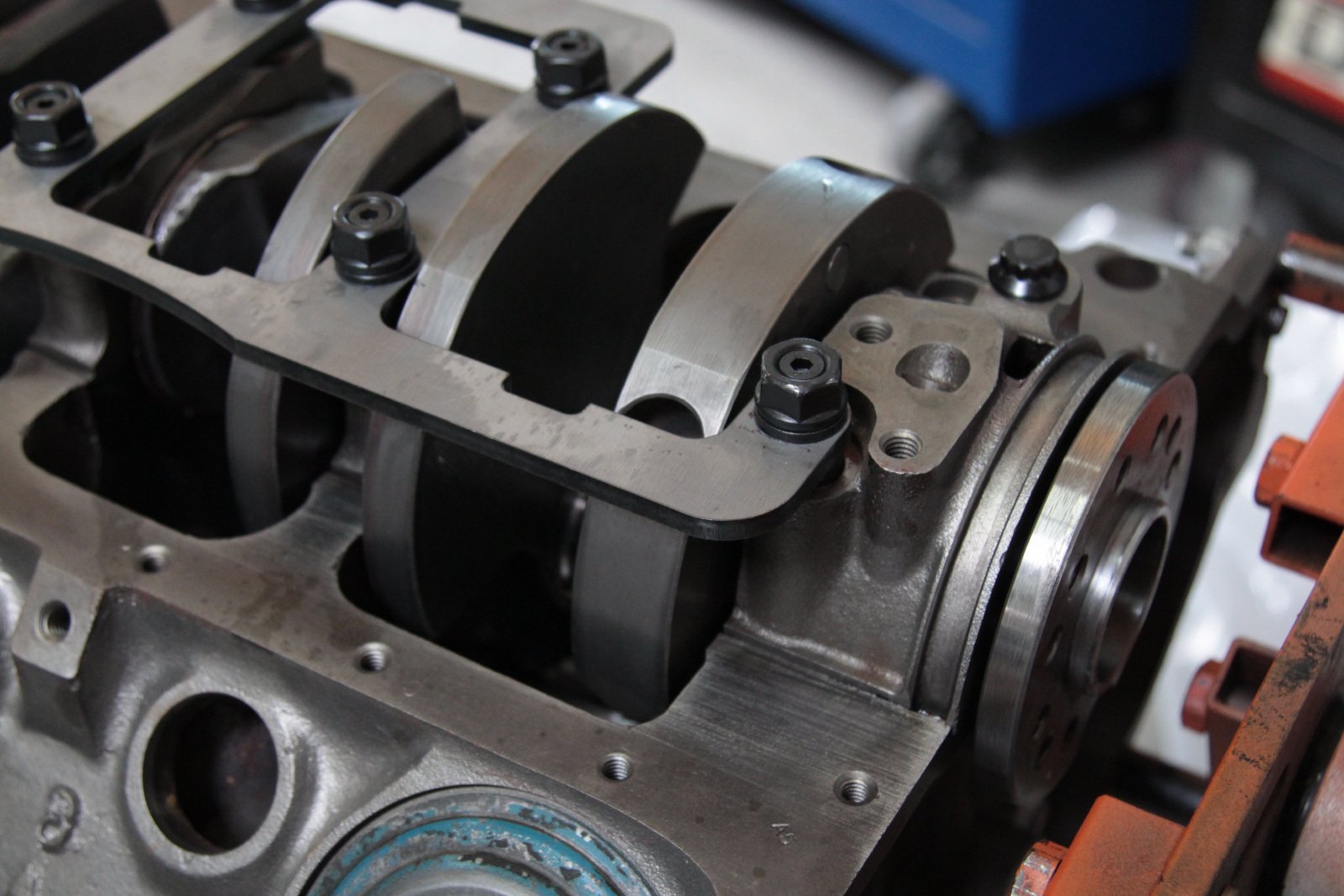

Unless you purchase an R3 race block — which will set you back a little over four large — or the R4 Pro-Stock race block, don't bother with a 4-bolt-main conversion kit on the 360. While it would seem to be stronger, you'll have to drill into thinner webbing for the new bolts at each main cap. Instead, we went with a Main Stud Girdle and had the machine shop work the main caps flush with the girdle. This kit, purchased from Hughes Engines, will provide us with some extra bottom end strength. The race blocks are nice, but we're building a street car with some meat and potatoes for road racing a couple times a year.

The advice we got was to find a 1970 to 1973 360ci block. While the Magnum is a decent engine, it’s the early blocks that we’ve found were more desirable to builders. Finding one is a chore, however, so don’t expect to start your build next week. Our search for a solid, buildable block took a few months, with prices ranging from a couple hundred bucks for a rusted out block to several hundred for a block four hours away that hadn’t been checked for cracks.

Keep in mind, if you buy a block with no guarantees and it doesn’t check out, you’re out some hard earned bucks, and you have to start over. So, take your time and try to get the seller to give you a little help – offer to pay a local shop to sonic test the block and have it magnafluxed. That way, you’re only out a extra few bucks, and not stuck with a junk block. We fortunately had a friend offer up a 1973 360ci block for a low price, with a promise to buy it back if it doesn’t check out – we got lucky. It’s good to have friends.

The most important thing you need to remember about a build is to stick to the plan. -Tom Lieb, Scat Crankshafts

We had it sonic tested to get all eight cylinders checked for any wear or imperfections, using sound waves to measure for material thickness and roundness of the cylinders. This process will also let you know if a .030 bore is going to be enough, or if you need to go further to get the cylinders round again. There will be one side of the cylinder that gets the most abuse, and that’s where some of the wear might show up. Sonic testing sounds high tech but has been done for quite some time and is an accurate test for measurements.

Our numbers were good, and we were in business with this block. We sent it off to the machine shop to get cleaned, decked, honed, and fitted for pistons and bearings. This process is going to run a few hundred bucks, and no parts can be ordered until you get the okay from the machine shop. Once we heard the block was buildable from the machine shop, we headed over to our friends at Scat Crankshafts for the rotating assembly.

We got some great ‘early’ advice from Tom Lieb, owner of Scat Crankshafts. “The most important thing you need to remember about a build,” he told us, “is to stick to the plan.” Any change you make to your build along the way just wastes money and time. Tom has been around building crankshafts since 1962, and this includes major automobile manufacturers to the tune of about 1,000 connecting rods and 100 crankshafts per day. He said, “We’re the only manufacturer who makes cast, forged, and billet crankshafts.”

Some have used a windage tray with this setup, but reports are that it's a bear to put it all together and may not work. Others have said they made 500-550 horsepower easily, without the girdle, and just adding studs. We're aiming higher - much higher - and the added insurance and support should work for us.

Planning Out Your First Engine Build

You’ll also need to find a reputable shop to do your build, especially one that knows your engine. Always ask around, check with friends, and do some research. We found a local shop, Motech Performance. The owner is a friend so we felt as comfortable spending our money as he did taking it. We discussed the plan with the shop, told him what we wanted to do, and he was on board with it.

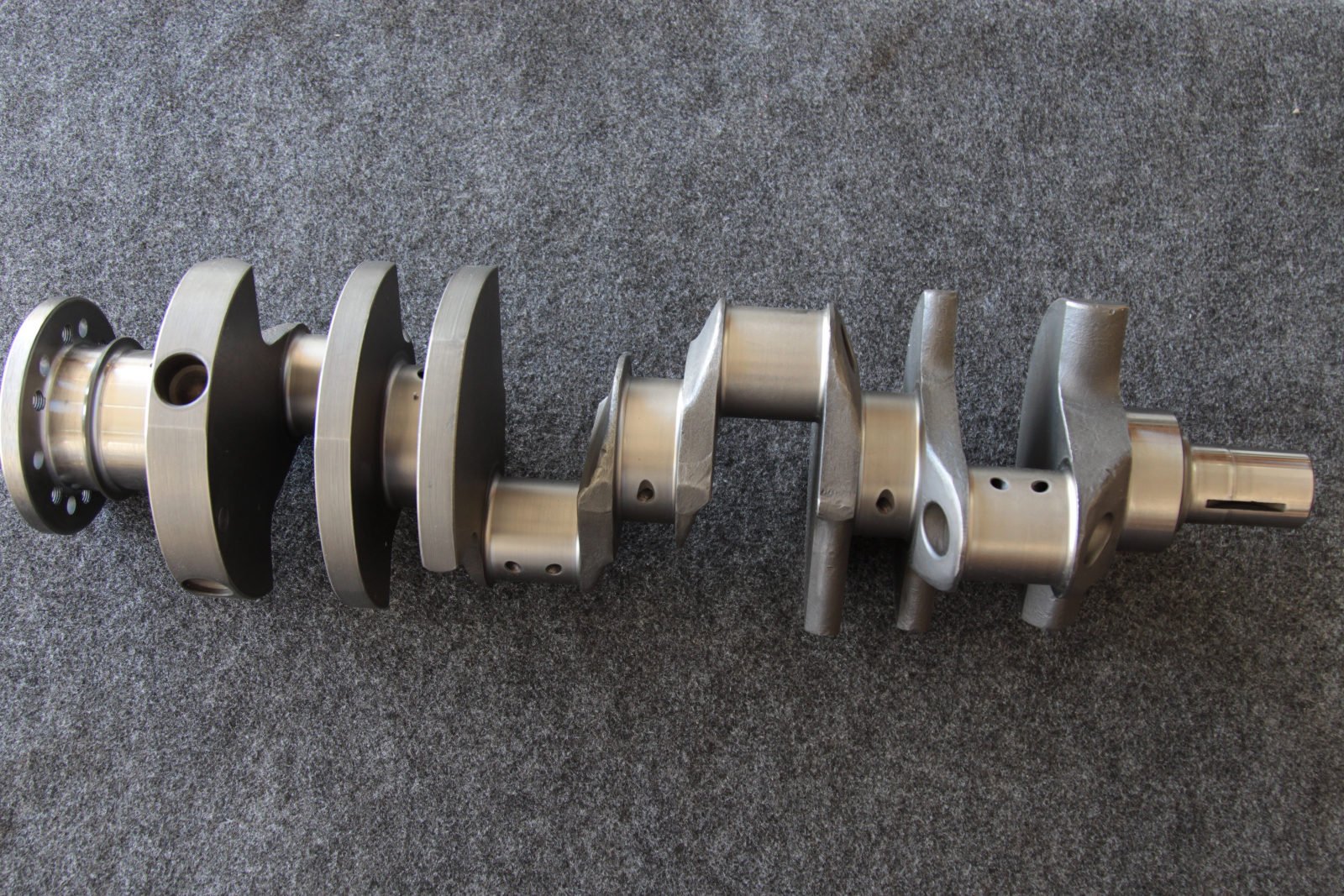

For our rotating assembly, we knew that the dependability of a Scat Crankshaft and Scat Rods would be the direction to take our build. The cast crank is fine for a street cruiser, but for the ponies we have planned, the forged crank was the only way to go. Tom Lieb tells us, "Scat Crankshafts is the only manufacturer that makes cast, forged, and billet crankshafts."

Before ordering a rotating assembly, figure out what you are aiming for with regards to horsepower. It’s also important to plan how you’re going to get to that figure: naturally aspirated, or what Tom calls “artificial air” – also known as boost. We laid out our plans for the car with regards to street and on-track performance, and came up with a horsepower figure we were aiming for.

If you’re going to be drag racing often, this is the time to talk about it. If you’re just going to be cruising to car shows and doing some hard parking, let them know. Whatever your plans are, Scat Crankshafts will put together a rotating assemble for your specific build. Tom said, “We put together a part number for the rotating assembly with all parts being equal.”

He continued, “So often, a guy buys a rotating assembly and each one has a part number designed around that build. No component is an oversell, and no part is stronger or any less than the next part. We balance the components to work together, all kits are based on the horsepower capability and the type of engine the customer is looking for.”

What Are Your Goals With Regards To Horsepower?

We are aiming for a respectable range, somewhere near Hellcat territory, and we are planning for some of that “artificial air.” As we stated, we’re not interested in bragging rights; besides, how often do people really get to enjoy their 1,200 horsepower builds?

“If you want to race a car twice a year, tune it for the track twice a year,” Tom said. “Don’t build a race car for the street. People build a 1,000-horsepower engine and they might hit a cars and coffee and get into it a little bit, but they never see that 1,000 horsepower leaving a parking lot.”

We’re not in the horsepower business. We’re in the business of making sure whatever horsepower you do have, that the engine can sustain it. -Tom Lieb

When putting together a rotating assembly, Tom reminds us the bottom end isn’t where the horsepower is made. “We’re not in the horsepower business,” he said. “We’re in the business of making sure whatever horsepower you do have, that the engine can sustain it.”

The absolute best advice given about our engine build came from Tom Lieb. He suggests that you determine what you want from the engine and stick to the plan — make your decisions ahead of time and don’t change it. We’d also like to add, don’t worry about what others say will or won’t work. Discuss your build with your parts suppliers, builder, and machine shop. Tell them what you are aiming for, and let them tell you what you might need. If you get the right people involved, they’ll steer you in the right direction.

Forged Or Cast: Which Is Better?

When we asked Tom about the differences between cast and forged components, he gave a technical description about cast that has to do with pouring molten metal in a mold for the basic shape. He told us, “It doesn’t have the same compact structure as a forging. It simply takes the shape of the mold it’s poured into.”

Then he explained the technical details of forging. That metal is poured into an ingot, heated up again and rolled into bars. “All of this working on the metal makes the grain more compact and establishes the grain structure,” he told us.

Internal or external balance? Anytime you’re building for power and plan to spin the engine at higher RPMs, an internal balance is preferable. It helps keep things in place and doesn’t put extra load on the block and bearings. An externally balanced crankshaft spinning above 5,000 RPM is a recipe for disaster, as it can create a ‘wobbling’ effect that transfers through the block to the flywheel.

We asked if there was a simpler explanation that is easier to understand, and Tom obliged us. Essentially, the difference between cast and forged is like comparing two groups of people, with each group given a circle, or shape, to stand in. One group is just standing there, filling the circle standing close together. The other group, however, is filled with more people pressed together and everyone is joining hands. The second group will have a stronger structure because of how the ‘grain’ (the people) – are bonded together. Forging compresses the metal and creates a stronger bond to handle more abuse than what a cast crankshaft will handle.

With regards to strength and durability, Tom tells us that the cast crank will have ⅓- less tensile strength, and endure about 1/3 to 1/2 less in fatigue life. You can expect the cast crankshaft to survive in a standard street build, but rule out the cast crank on any build with artificial air. If you’re thinking about a stroker, Tom tells us that the component parts cost roughly the same between a stock build and a stroker. It really boils down to the build, your goals, and what compression ratio you want. This also brings the cylinder head and air flow into the equation, so knowing what cylinder head you’re using is also important.

Regarding horsepower, there are variables that Scat uses to determine whether you should go with a cast, forged, or even a billet crankshaft. Billet is for the big guns, and it’s overkill for our goals. Tom tells us that typical, naturally-aspirated builds are perfect for a cast crankshaft. This would be a mild street build, or even a big block upwards of 500 horsepower. But when you’re going to be adding a supercharger or turbocharging, then he recommends the forged crankshaft. If you’re heading past 900 horsepower, that’s when Tom suggests looking into a billet crankshaft.

Scat manufacturers its own connecting rods. Each application is considered, and no component of the rotating assembly is going to be the strongest, according to Lieb.

H Beam or I Beam Rods: Which Is Best?

When it comes to connecting rods, the talk among those who brag about power is to get H beam rods. But, Tom explained that rod choices are made with regards to power output. He says there’s a purpose for the different designs. I beam rods are not as strong as the H beam equivalent; some forged I beam rods can be as strong, but they are heavier. He said, “When the choice is having a rod that is lighter and stronger, the H beam rod will always come out on top.”

One of the things our customers buy is our knowledge. -Tom Lieb

This also brings us back to the differences we outlined in crankshaft choices; forged rods will be more costly than cast, and the decision is best left to the experts. Let the staff at Scat determine what is best for your build. Remember, you don’t want to have a stronger rod than what the cast crankshaft will handle, and they can put together a rotating assembly with equal parts. As Tom said, “One of the things our customers buy is our knowledge.”

While the main function of the connecting rod is to connect the piston to the crankshaft, there's much more to making a set of rods. Weight, strength, and piston-pin style needs to be determined before the rods can be selected.

Filling The Holes With JE Pistons

Normally, Scat will put together an entire rotating assembly using various pistons from name-brand manufacturers. Since we had some specifics with our build, the pistons aren’t off-the-shelf parts, and for that we reached out to JE Pistons with our specs to build our pistons. We had a few questions, so we spoke to Evan Perkins and he gave us the low down on JE quality.

Q: When choosing pistons, what determining factors are used for selecting cast vs. forged?

A: Forged pistons are always preferred in a performance build. The base material, whether 4032 or 2618 material, is denser and stronger than cast aluminum and is going to be more tolerant of engine speed, detonation – something that will inevitably occur in a performance engine – and overall cylinder pressure. For anything short of a stock rebuild, forged is the only way to go.

Q: If forged is a more expensive process, why does JE not have cast/hypereutectic pistons?

A: Forging requires dedicated machinery such as a massive forging press, which is two stories tall and can deliver hundreds of tons of pressure to squish/form aluminum into a die yielding the net shape of the piston. We do this in-house, at our Ohio manufacturing plant. Inevitably, this process adds more cost than simply pouring molten aluminum into a mold, such as the case with cast and hypereutectic pistons. Again, for performance applications, castings don’t offer near the strength of a forged piston and that is what we focus on.

For performance applications, castings don’t offer near the strength of a forged piston and that is what we focus on. -Evan Perkins, JE Pistons

Q: Can you explain dished vs. flat-top vs. domed pistons, where each is beneficial and how they affect power?

Piston crown shape – dish/dome/flat-top – is all a function of delivering the desired compression ratio. The cylinder’s total swept volume, divided by the amount of available space (measured in CCs) at top dead center (TDC) is the compression ratio. By building a dome, dish, or flat-top piston crown with only valve reliefs, we can adjust the amount of space at TDC, to create a lowered compression ratio for boost, or a higher compression ratio for naturally aspirated engines.

JE Pistons only offers forged pistons, and all are made at its Ohio manufacturing plant.

No part in an engine is an island. Everything must operate in a closed ecosystem with finite rules and measurements. One of those measurements is deck height. Once the piston compression height (height of the pin-bore centerline) reaches the top of the block deck, it can go no further. Therefore a dome is sometimes necessary to decrease the amount of space in the combustion chamber at TDC to increase compression ratio, while keeping the piston below the top of the deck surface.

In the reverse application, where the builder wants to lower compression ratio, simply shortening the piston’s compression height will achieve that goal. However, it isn’t ideal. Lowering the piston overall creates a very wide combustion area that asks the flame front, which travels from the spark plug outward, to move a larger distance before the entire mixture is ignited. This can make the engine more prone to knock. In this situation, where the builder desires a significantly lower compression ratio than stock, a dished or inverted dome piston is preferable to keep combustion more centralized and efficient.

Q: Pressed or floating pins: can you explain the differences?

A: Floating wrist pins are the performance standard and the only option we produce. Pressed pins are ancient technology at this point, and were a means by OEM manufacturers to mass produce rotating-assembly components cheaply. A floating pin is going to offer reduced friction and better durability in all cases.

While you may have heard someone boast about having ‘flat top pistons’, Evan Perkins explains to us that the piston crown shape is all part of the process of delivering the desired compression ratio. We asked for a lower compression ratio, and this dished piston will help keep the combustion more centralized and efficient than simply producing a shorter piston.

Q: What compression ratios do you recommend for a performance build?

A: Compression ratio is unique to the engine application and not a set threshold based on fuel. An LS engine may tolerate a 12:1 compression ratio on premium pump fuel, where a first-generation small block starts to get fussy at 10.5:1. Really, it is a function of combustion-chamber design, cylinder-head material, cam timing, ignition system, and fuel atomization/distribution. Tuning also plays a significant role.

Generally, NA engines are going to be between the 10:1 to 12.5:1 range and boosted engines will fall into the 8.5:1 to 10:1 range. As combustion becomes more efficient with technologies such as direct injection and ignition, we’ve seen these ratios creep toward the top of the range even with boost. Often, it is the precise control of the EFI and variable valve timing that allow such high compression without knock. Older engines, obviously, don’t benefit from those technologies.

For a boosted application, 8.5:1 used to be the standard, but the ratio has crept up and is approaching 9.5:1 on average, higher when using fuels such as E85. The general advice we give to customers is to keep compression ratio conservative. Unless you are chasing e.t.s professionally, it is far easier to add a couple of pounds of boost at the top end to satisfy your power requirements than have detonation from too much static compression ratio.

Our short block build is done. Next we install the Edelbrock Magnum heads and a Comp Cams valvetrain in part 2 of our small-block Mopar build.

This information from Evan helps us to understand a little bit more about pistons, and convinces us that it’s always best to provide the details of your build – including cylinder head specs – and let the professionals determine what piston is best for your application. It goes along with what Tom Lieb stated earlier about making all parts equal in a rotating assembly.

If you’re ordering part numbers from an online store, you better make sure you know what you’re doing or you could end up with a rotating assembly that doesn’t want to play nice inside the block. The last thing you want is your connecting rods to come knocking, so leave it up to the pros to help plan out your build and recommend components. It’s a big investment, and companies like JE Pistons and Scat Crankshafts are there to help you build the perfect beast.

We’ll continue on with the top end build, and then share some of the hidden or (lesser-seen) components we used to build our 408ci stroker small-block. It’s coming together and looking great, and we can’t wait to hit the track again.