We know that forcing air into an engine can enhance the combustion process and increase power. The three most popular power-adders are mechanically-driven superchargers, exhaust-driven turbochargers, and nitrous oxide. There’s actually a fourth — compressed air supercharging. But the technology is complex and the system is costly. Of all of these, nitrous oxide is the most cost-effective power-adder, especially for a street car.

First discovered in 1744 by James Priestly, a British scientist, nitrous oxide (N2O) consists of two parts nitrogen and one part oxygen. it’s been employed as an anesthetic by dentists since the mid-1850s.

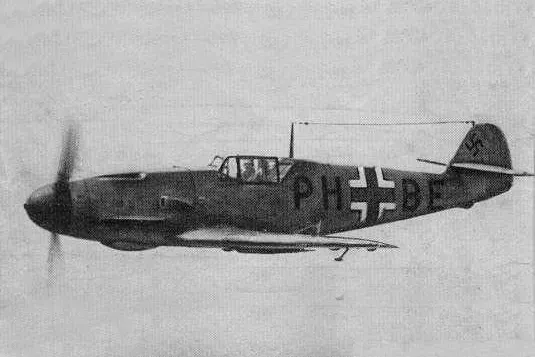

The first use of nitrous oxide as a performance enhancement occurred in World War II when the German Luftwaffe used it in Me-109 fighters for an advantage in high-altitude combat.

In the 1970s, nitrous oxide kits began to appear in the automotive aftermarket, with one of the most popular being manufactured by the fledgling company founded by Mike Thermos and Dale Vaznaian, Nitrous Oxide Systems, Inc. — better known by the acronym “NOS.” The company was acquired by Holley at the pinnacle of “The Fast and The Furious” movie franchise’s focus on nitrous, and the brand was also licensed for an energy drink.

Thermos, who is often referred to as “the Godfather of Pro Mod,” returned to his roots in 2004 by forming Nitrous Supply, Inc., and has been providing components to racers and other manufacturers ever since. He’s also developed a variety of kits for street applications.

Nitrous Oxide: Old Ways & New

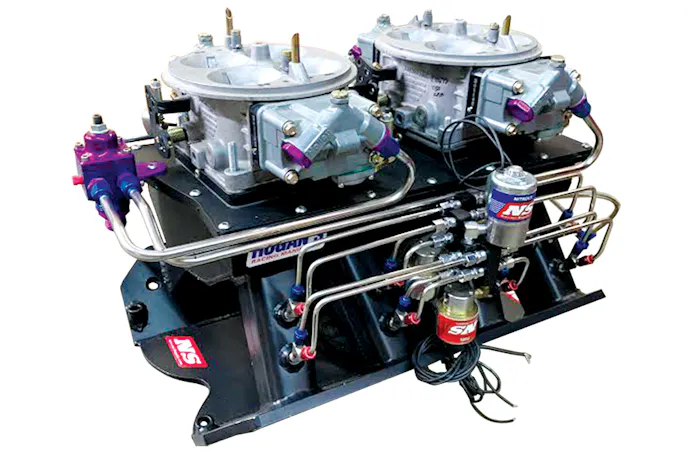

Back in the pre-EFI era, adding nitrous oxide to the engine was mostly accomplished by installing a plate beneath the carburetor that had spray bars for the nitrous and fuel — with jets employed to control the flow of each. With the quest for increased power came the introduction of “fogger” nozzles placed in intake manifold to facilitate tuning each cylinder independently. Multi-stage systems are used in racing.

The systems that have been developed for use with electronically fuel injected engines — prevalent since the late 1980s — are categorized as “wet” and “dry.” The wet system requires getting the necessary extra fuel, typically through tapping into the engine’s fuel rail. Solenoids are activated to introduce both nitrous and fuel into the engine. A fogger-type nozzle that distributes both gas and nitrous is installed adjacent to the throttle body.

A dry system depends on the vehicle’s ECU to adjust the fuel flow to compensate for the added oxygen. The single-purpose nozzle is easily attached to the intact tract.

What’s Best For Your Application?

We know that today’s humongous Pro Mod motors can produce power approaching 3,000 horsepower. So what can be expected from a street application?

First, let’s examine the basics. The power increases from superchargers and turbochargers are a function of how much boost is created — typically driven by engine RPM. Nitrous is “all in” at the hit. Since the added power is prevalent at lower rpm, the “feel” can be equated to increasing the engine’s displacement. Note that timers can be employed to control the flow.

In popular lexicon, a “100 shot” equates to a kit designed to produce 100 extra horsepower through the added oxygen and fuel. So, how big a “shot” can you add to an engine?

As a rule of thumb, a standard engine in good shape can accommodate a 40 percent increase in power. So an engine rated at 400 horsepower normally aspirated should be able to handle a 150 shot nitrous kit. Larger power outputs dictate the use of high-performance engine components like forged aluminum pistons, forged steel rods, etc.

The ignition curve is also a factor (some retarding required). Obtaining the optimum fuel/air ratio is important in making horsepower. The baseline stoichiometric measure for a gasoline engine is about 14.7:1. In other words, for every one gram of fuel, 14.7 grams of air are required for complete combustion. However, for most normally aspirated engines the ideal power ratio is 12.5-13.1. Dyno testing will confirm this. Of course, a mixture that’s too rich will reduce the power potential. Conversely, an overly lean condition can cause severe engine damage. Most quality nitrous kits come with a selection of jets so you can optimize the air/fuel mixture.

Introducing The Added Nitrous & Fuel

There’s also the factor of how the nitrous and extra fuel are introduced into the engine. When nitrous gained popularity in the “carburetor era” the popular systems featured a plate installed below the carb that directed the mixture into the plenum of the intake manifold. In a quest to gain efficiency and power, “fogger” systems were developed that facilitated controlling the nitrous/fuel mixture on a cylinder-to-cylinder basis. Serious racers now employ multiple stages to meter the mixture going down the track.

Standard bottle pressure is 950 psi. As you might suspect, the pressure will start to dwindle as you use up the nitrous. Figure that the pressure from a typical 10-lb. bottle will start dropping in the run. That’s why some racers prefer a 15-lb. bottle.

Temperature is also a factor, as “electric blanket” type bottle warmers are employed in colder environments. Never apply an open flame heat source to the bottle, as there are

documented cases of bottles exploding from the metal annealing, and too

much internal pressure.

Temperature does play an important role in the effectiveness of nitrous oxide. When it enters the intake tract it’s minus 127 degrees (F). This serves to reduce the inlet air temperature, which in itself brings more power. It’s postulated that for every 10-degree reduction in the temperature of the charge power is increased by one percent.

Should you opt for installing a nitrous oxide system, getting refills will be part of the equation. A dealer will transfer the N2O from large “mother bottles” to smaller 10-, 12-, 15- and 20-lb. sizes common to street applications. The nitrous is added in liquid form and bottle ratings based on the actual weight; refills are sold on a per-pound basis.

For non-medical use, commercial nitrous oxide contains a trace of sulfur dioxide to dissuade recreational use (yes, nitrous is called “laughing gas).

So there you have it. It’s easy to add some “muscle” to your street machine with nitrous —and because it’s “on demand” — you can cruise normally and economically until that moment when extra power is desired.

As Mike Thermos is fond of saying, “Nitrous oxide is a cheap date.”

You might also like

Student-Built ’68 Camaro Gets A New Beginning

Remarkably, the students designed and built the cantilever rear suspension themselves and used QA1 coilover shocks.